During the Covid-19 pandemic, people living in cities likely observed and appreciated the better air quality. Instead of the air having the unpleasant scent and taste as if it came from a car’s exhaust, it was noticeably fresher and definitely cleaner.

For instance, in London, air quality tests revealed a 22% average daily decrease in nitrogen dioxide (NO2). Since NO2 is linked to breathing and heart issues, this reduction is a great improvement.

It’s no wonder that these findings have strengthened the push to replace vehicles running on fossil fuels with electric vehicles powered by batteries.

Unfortunately, the switch from all combustion engine vehicles to lithium-powered electric vehicles (EVs) isn’t as straightforward as it seems. This is because numerous studies have shown that the process of mining lithium from brine is harmful to the environment. Additionally, the use of toxic materials like cobalt in lithium batteries means that EVs aren’t exactly the eco-friendly solution they’re often made out to be.

I won’t delve too deep into this, but here are a few important points to consider.

Firstly, the production of an EV results in a significant carbon footprint, generating over a ton more greenhouse gas compared to a petrol-powered vehicle. However, it’s worth noting that the lifetime carbon footprint of EVs is half that of vehicles powered by fossil fuels, which is a positive aspect. While EVs themselves don’t pollute the atmosphere, the production of the electricity needed to power them does, unless it comes from renewable sources.

Costing Five Times More

Secondly, there’s a paradox when it comes to recycling old lithium batteries in an environmentally friendly way. In simple terms, lithium obtained from recycling is five times more expensive than lithium produced through the less eco-friendly but cheaper method of brine mining.

So, could there be more environmentally sustainable and economically viable alternatives, such as ethanol fuel?

There are numerous instances where ethanol fuel is utilized, with Brazil being one of the largest examples. Over 70% of cars in Brazil can operate on a blend of ethanol and petrol.

Ethanol, when derived from sugarcane, has emissions that are up to 90% lower than those of petrol or diesel. The swift shift to widespread ethanol use in Brazil offers valuable insights on several levels.

The remarkably quick acceptance of ethanol by drivers involved collaboration between sugarcane farmers, ethanol distillers, local and international car manufacturers, and environmental groups. The outcome was a fuel that was 50% cheaper than petrol, but is it more eco-friendly?

Supporters of ethanol argue that when it’s sourced from sugarcane, it’s a sustainable fuel, with direct emissions up to 90% lower than those of petrol or diesel. However, just like the production of electricity for battery-powered cars can have a negative environmental impact, so can the production of ethanol, and that’s the issue.

Danger to the Rainforest

When ethanol, made from sugarcane, became popular in Brazil, the government wisely enacted a rule that sugarcane farming was not allowed on Amazon rainforest land. Unfortunately, this rule was overturned about half a year ago. Now, land from the invaluable rainforest is being used to produce car fuel. This is hardly a move that aligns with environmental responsibility.

Before we conclude that ethanol won’t be the frontrunner in the race for eco-friendly car fuel, let’s consider some alternative methods of producing ethanol.

Research from the University of Michigan suggests that corn crops used for ethanol production only absorb about 37% of the carbon that the fuel later emits into the atmosphere. So, this isn’t exactly a green revolution.

Experts in the field generally agree with this view, believing that the crops don’t absorb enough carbon to offset what’s emitted from car exhausts. From an emissions standpoint, biofuels aren’t any better than petrol and diesel.

However, before we dismiss ethanol due to its questionable environmental impact, it’s only fair to mention that while corn and sugarcane-based ethanol do have a negative effect, there’s also cellulose-derived ethanol, which is known to be much more eco-friendly. The issue with this alternative is that it remains too expensive until large-scale production becomes feasible.

Recycle Lithium from EV

So, if we set aside ethanol, what about overcoming the hurdles of recycling lithium batteries? What’s the issue?

Fundamentally, it’s a matter of cost. Recycling lithium batteries isn’t economically appealing because the cells don’t contain much lithium. However, what excites those in the recycling business is the financial benefit of extracting the valuable cobalt and nickel from the batteries. As a result, almost none of the lithium used in batteries is fully recycled.

But this could be changing. For instance, consider the research that won the 2019 Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) is making progress on a project called Libre, which aims to find a process that recovers materials from what they call the “black mass” – essentially, the black powder composed of elements found in the large batteries used in EVs, particularly the battery’s electrodes. Depending on the battery’s construction, these materials can include nickel, cobalt, manganese, lithium, and carbon.

Currently, recycling lithium from EV batteries isn’t financially appealing, as indicated in a report from Bloomberg analysts. However, the research team is confident that this will change in a few years. How? They predict that the number of EVs on our roads will increase over the next five years. Research suggests that by 2025, there will be approximately 14 million EVs globally, with 6.5 million in Europe.

Despite the optimism and forward-thinking nature of this Norwegian research, many still view lithium recycling as a significant challenge. One such person is Dr. Gavin Harper, a Faraday Research Fellow at the University of Birmingham.

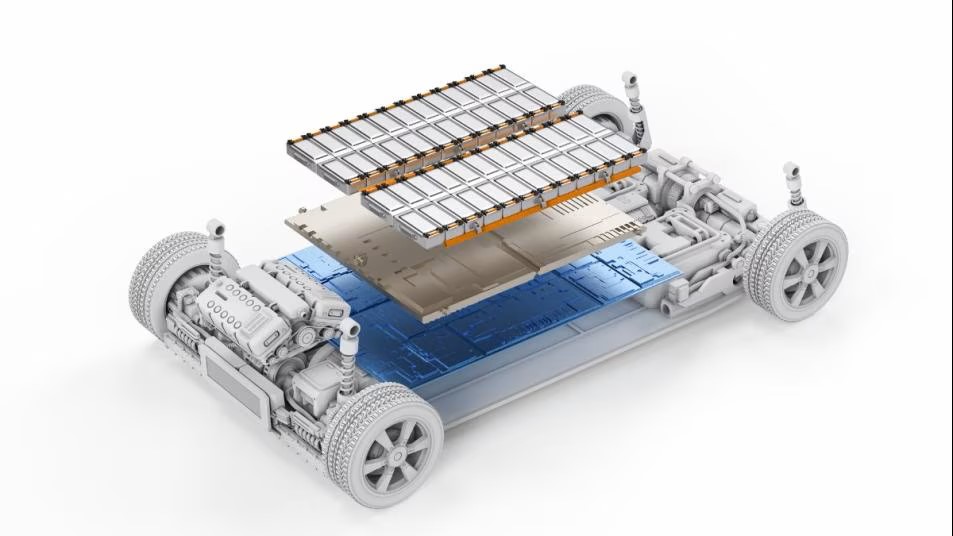

He believes the recycling challenge is complex, partly due to the vast diversity in the chemistries, shapes, and designs of the lithium-ion batteries used in EVs. Individual cells are formed into modules, which are then assembled into battery packs. To recycle these efficiently, they must be disassembled, and the resulting waste streams separated.

But academia isn’t the only sector interested in recycling – car manufacturers are too, but only if it provides a source of low-cost material that can be reprocessed into new batteries.

Researchers at Princeton University have investigated how a direct cathode-recycling process would compare to other recycling processes in terms of greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption.

This battery recycling method would focus on preserving the cathode materials so they can be used in future batteries. While all lithium-ion batteries use lithium to carry the charge, their cathodes – which store the lithium ions when the battery is discharged – can be made from various materials, such as nickel, manganese, or cobalt.

The researchers analyzed the lithium-ion formulations commonly found in EV batteries. They found that for cathodes containing metals like nickel, manganese, and cobalt, direct cathode recycling could reduce the greenhouse gas emissions associated with manufacturing new cells from these materials and could potentially be economically competitive with traditional cathode manufacturing.

So, it seems that lithium recycling could eventually become a more financially viable option. However, it still needs to convince the financial decision-makers that it’s a worthwhile alternative to repurposing old EV batteries for uses that require less battery performance than powering cars.

Two factors are at play here. Firstly, the global stockpile of these batteries will reach 3.5 million by 2025. Secondly, many EV batteries, which are no longer suitable for vehicle propulsion, still have between 65-70% of their operating capacity available.

It’s not surprising to see that in Japan, Nissan is repurposing batteries to power street lights, while in France, Renault is using old car batteries as backup for elevator systems. In the US, GM is using retired Chevy Volt batteries to support its data center. Beyond these, there are many other uses for discarded EV batteries, such as storing solar energy and powering homes by taking advantage of off-peak electricity charging facilities.

When it comes to the race for environmental sustainability, there’s no doubt that improving the efficiency of lithium recycling is a significant technical challenge. Repurposing EV batteries seems to be leading the way. As for ethanol as a car fuel, in my view, it’s trailing behind on the starting line.

Read more: